Problem 1

What is the value of $\frac{(2112-2021)^2}{169}$?

$\textbf{(A) } 7 \qquad\textbf{(B) } 21 \qquad\textbf{(C) } 49 \qquad\textbf{(D) } 64 \qquad\textbf{(E) } 91$

Solution

$\frac{91^2}{13^2}=7^2=\boxed{\textbf{(C) } 49}$.

Problem 2

Menkara has a $4 \times 6$ index card. If she shortens the length of one side of this card by $1$ inch, the card would have area $18$ square inches. What would the area of the card be in square inches if instead she shortens the length of the other side by $1$ inch?

$\textbf{(A) }16\qquad\textbf{(B) }17\qquad\textbf{(C) }18\qquad\textbf{(D) }19\qquad\textbf{(E) }20$

Solution

$(4-1) \times 6 = 18$ $4 \times (6-1) = \boxed{\textbf{(E) } 20}$

Problem 3

Mr. Lopez has a choice of two routes to get to work. Route A is $6$ miles long, and his average speed along this route is $30$ miles per hour. Route B is $5$ miles long, and his average speed along this route is $40$ miles per hour, except for a $\frac{1}{2}$-mile stretch in a school zone where his average speed is $20$ miles per hour. By how many minutes is Route B quicker than Route A?

$\textbf{(A)}\ 2 \frac{3}{4} \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 3 \frac{3}{4} \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 4 \frac{1}{2} \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 5 \frac{1}{2} \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 6 \frac{3}{4}$

Solution

$60(\frac{6}{30}-\frac{4.5}{40}-\frac{0.5}{20})=12-6.75-1.5=3.75=\boxed{\textbf{(B) } 3 \frac{3}{4}}$.

Problem 4

The six-digit number $\underline{2},\underline{0},\underline{2},\underline{1},\underline{0},\underline{A}$ is prime for only one digit $A.$ What is $A?$

$(\textbf{A}): 1\qquad(\textbf{B}) : 3\qquad(\textbf{C}) : 5 \qquad(\textbf{D}) : 7\qquad(\textbf{E}) : 9$

Solution

Test by 3 eliminates $1,7$. Test by 5 eliminates $5$. Test by 11 eliminates $3$. (Recall that $10^{2n+1} \equiv -1$ \pmod{11}$ while $10^{2n} \equiv 1$ \pmod{11}$)

Hence, $A=\boxed{\textbf{(E) } 9}$.

Problem 5

Elmer the emu takes $44$ equal strides to walk between consecutive telephone poles on a rural road. Oscar the ostrich can cover the same distance in $12$ equal leaps. The telephone poles are evenly spaced, and the $41$st pole along this road is exactly one mile ($5280$ feet) from the first pole. How much longer, in feet, is Oscar’s leap than Elmer’s stride?

$\textbf{(A) }6\qquad\textbf{(B) }8\qquad\textbf{(C) }10\qquad\textbf{(D) }11\qquad\textbf{(E) }15$

Solution

Draw a diagram. Picture 41 points, 40 gaps. Then each gap is $\frac{5280}{40}=132$ feet. Then the gap is $132(\frac{1}{12}-\frac{1}{44})=11-3=\boxed{\textbf{(B) }8}$ feet.

Problem 6

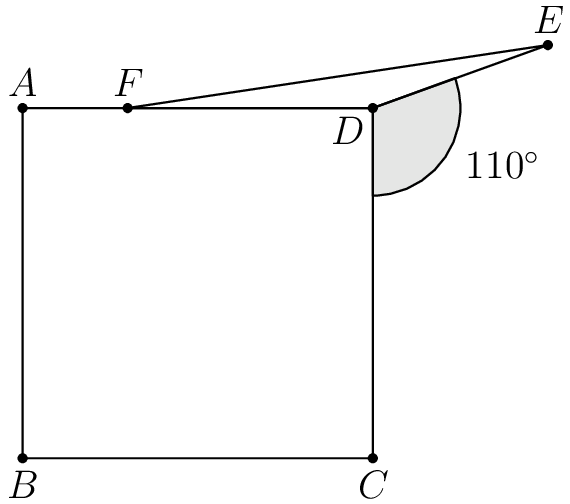

As shown in the figure below, point $E$ lies on the opposite half-plane determined by line $CD$ from point $A$ so that $\angle CDE = 110^\circ$. Point $F$ lies on $\overline{AD}$ so that $DE=DF$, and $ABCD$ is a square. What is the degree measure of $\angle AFE$?

$\textbf{(A) }160\qquad\textbf{(B) }164\qquad\textbf{(C) }166\qquad\textbf{(D) }170\qquad\textbf{(E) }174$

Solution

$\angle FDE = 360-110-90=160$, $\angle DFE = \frac{180-160}{2}=10$. $\angle AFE = 180-\angle DFE=180-10=\boxed{\textbf{(D) }170}$.

Problem 7

A school has $100$ students and $5$ teachers. In the first period, each student is taking one class, and each teacher is teaching one class. The enrollments in the classes are $50, 20, 20, 5,$ and $5$. Let $t$ be the average value obtained if a teacher is picked at random and the number of students in their class is noted. Let $s$ be the average value obtained if a student was picked at random and the number of students in their class, including the student, is noted. What is $t-s$?

$\textbf{(A)}\ {-}18.5 \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ {-}13.5 \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 0 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 13.5 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 18.5$

Solution

$t=\frac{1\cdot 50 + 1\cdot 20 + 1\cdot 20 + 1\cdot 5 + 1\cdot 5}{5}=\frac{100}{5}=20$ $s=\frac{50\cdot 50 + 20\cdot 20 + 20\cdot 20 + 5\cdot 5 + 5\cdot 5}{50+20+20+5+5}=\frac{3350}{100}=33.5$.

Hence $t-s=20-33.5=\boxed{\textbf{(B) } -13.5}$.

Problem 8

Let $M$ be the least common multiple of all the integers $10$ through $30,$ inclusive. Let $N$ be the least common multiple of $M,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,$ and $40.$ What is the value of $\frac{N}{M}?$

$\textbf{(A)}\ 1 \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 2 \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 37 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 74 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 2886$

Solution

The only new factors introduced are from higher powers and new primes. Here, we get $2$ from $32=2^5$, and $37$. All others have been covered earlier, so we get $\frac{N}{M}=2 \cdot 37 = \boxed{\textbf{(D) } 74}$.

Problem 9

A right rectangular prism whose surface area and volume are numerically equal has edge lengths $\log_{2}x, \log_{3}x,$ and $\log_{4}x.$ What is $x?$

$\textbf{(A)}\ 2\sqrt{6} \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 6\sqrt{6} \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 24 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 48 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 576$

Solution

I bashed with $y:=\log x$, $a:=\log 2$, $b:=\log 3$, but MRENTHUSIASM’s solution is much more efficient. You convert to the same base so operations are easy. So let $a:=\log_x 2$, $b:=\log_x 3$, and $c:=\log_x 4$. Then we get:

$$2\left(\frac{1}{ab}+\frac{1}{bc}+\frac{1}{ca}\right)=\frac{1}{abc}$$Clearing denominators, we get that

$$2(a+b+c)=1$$, so that unfolding, we get $2(\log_x 2+\log_x 3+\log_x 4)=1$, so that after using log rules we get $\log_x (2\cdot 3\cdot 4)^2=\log_x 576=1$, gielding $x=\boxed{\textbf{(E) }576}$.

Problem 10

The base-nine representation of the number $N$ is $27{,}006{,}000{,}052_{\text{nine}}.$ What is the remainder when $N$ is divided by $5?$

$\textbf{(A) } 0\qquad\textbf{(B) } 1\qquad\textbf{(C) } 2\qquad\textbf{(D) } 3\qquad\textbf{(E) }4$

Solution

$2+5\cdot 9+6\cdot 9^6+7\cdot 9^9+2\cdot 9^10 \equiv ? \pmod 5$. Let’s find the digit cycle of $9^n \pmod 5$.

- $9 \equiv 4 \pmod 5$

- $9^2 \equiv 16 \equiv 1 \pmod 5$

So odd gives $4$, even gives $1$ as residue. We simplify:

$2+6+7\cdot 4+2 \equiv \boxed{\textbf{(D) 3}} \pmod 5$.

(I read the solutions and realized I could’ve set $9 \equiv -1 \pmod 5$)

Problem 11

Consider two concentric circles of radius $17$ and $19.$ The larger circle has a chord, half of which lies inside the smaller circle. What is the length of the chord in the larger circle?

$\textbf{(A)}\ 12\sqrt{2} \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 10\sqrt{3} \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ \sqrt{17 \cdot 19} \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 18 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 8\sqrt{6}$

Solution

Draw a diagram. Let the chord length be $l = 4s$. Drawing radii to the intersections between the chord and the circles, we have by Pythagoras that $19^2-(2s)^2=17^2-s^2$. Solving, we get $3s^2=(19-17)(19+17)$, or $s=2\sqrt{6}$. Hence, the length of the chord is $4\cdot 2\sqrt{6}=\boxed{\textbf{(E) } 8\sqrt{6}}$.

Problem 12

What is the number of terms with rational coefficients among the $1001$ terms in the expansion of $\left(x\sqrt[3]{2}+y\sqrt{3}\right)^{1000}?$

$\textbf{(A)}\ 0 \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 166 \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 167 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 500 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 501$

Solution

To be rational (here, equivalently integer), the power must be a multiple of $3$ for the first term, and a multiple of $2$ for the second term. Let $a:=\sqrt[3]{2}x$ and $b:=\sqrt{3}y$.

Binomial expansion:

$$(a+b)^{1000}=\text{integer}\cdot a^k\cdot b^{1000-k}$$Hence, we need $k\equiv 0\pmod 3$ and $1000-k \equiv 0 \pmod 2 \iff k\equiv 0\pmod 2$, or $k\equiv 0\pmod 6$. Hence, $\lfloor \frac{1001}{6} \rfloor + 1 = \boxed{\textbf{(C) } 167}$.

Problem 13

The angle bisector of the acute angle formed at the origin by the graphs of the lines $y = x$ and $y=3x$ has equation $y=kx.$ What is $k?$

$\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} \qquad \textbf{(B)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{7}}{2} \qquad \textbf{(C)} \ \frac{2+\sqrt{3}}{2} \qquad \textbf{(D)} \ 2\qquad \textbf{(E)} \ \frac{2+\sqrt{5}}{2}$

Solution

Notice that for vectors of equal length, their average will bisect the angle between them. Hence, let $\overrightarrow{(1,3)}$ have length $\sqrt{1^2+3^2}=\sqrt{10}$, so we scale to match this length: $|\overrightarrow{(1,1)}|=\sqrt{2}$, $|\sqrt{5}\overrightarrow{(1,1)}|=\sqrt{10}$.

Then the average of the two vectors is $\overrightarrow{(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2},\frac{3+\sqrt{5}}{2})}$.

Then the slope is $\tan \theta=\frac{3+\sqrt{5}}{1+\sqrt{5}}=\frac{(\sqrt{5}+3)(\sqrt{5}-1)}{4}=\frac{5-\sqrt{5}+3\sqrt{5}-3}{4}=\frac{2+2\sqrt{5}}{4}=\boxed{\textbf{(A) } \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}$.

Also why is the golden ratio here again

Problem 14

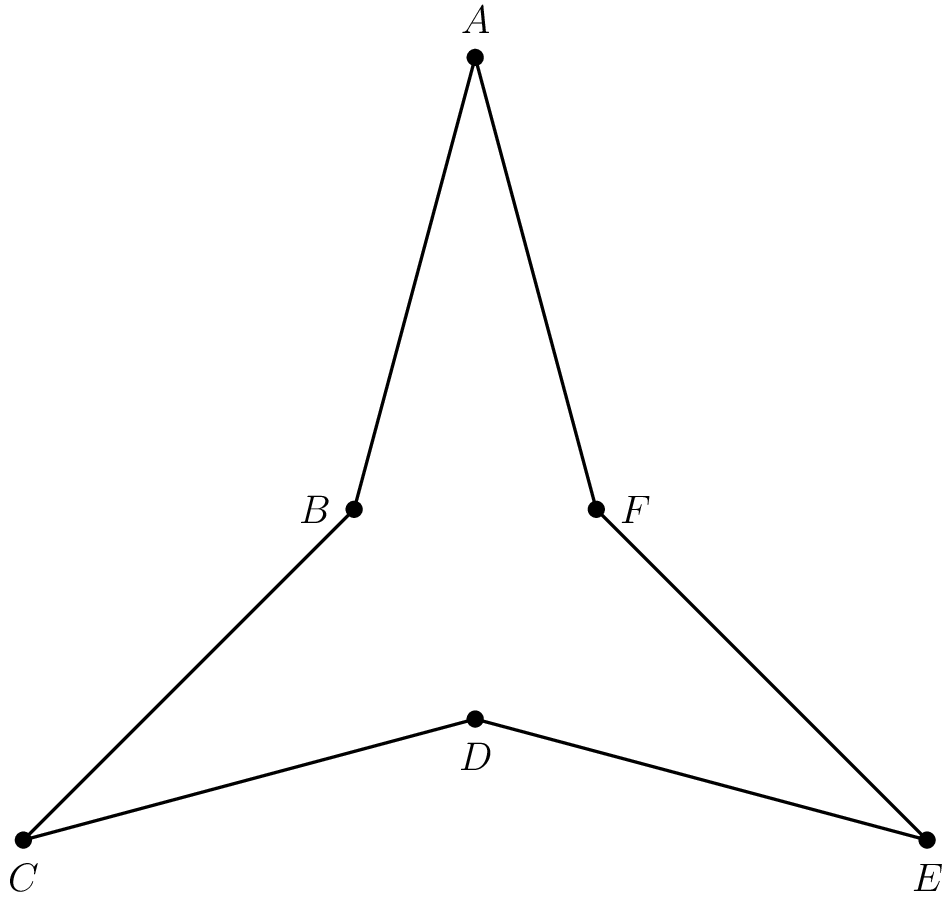

In the figure, equilateral hexagon $ABCDEF$ has three nonadjacent acute interior angles that each measure $30^\circ$. The enclosed area of the hexagon is $6\sqrt{3}$. What is the perimeter of the hexagon?

$\textbf{(A)} : 4 \qquad \textbf{(B)} : 4\sqrt3 \qquad \textbf{(C)} : 12 \qquad \textbf{(D)} : 18 \qquad \textbf{(E)} : 12\sqrt3$

$\textbf{(A)} : 4 \qquad \textbf{(B)} : 4\sqrt3 \qquad \textbf{(C)} : 12 \qquad \textbf{(D)} : 18 \qquad \textbf{(E)} : 12\sqrt3$

Solution

Let the side length be $s=AB$. The perimeter becomes $6s$. Then the area of the three triangles like $\triangle ABF$ is $3\cdot \frac{1}{2}s^2 \sin 30^\circ = \frac{3}{4}s^2$. Now, consider the equilateral triangle. We have 2 sides and 1 (nice) angle, and the formula of the equilateral triangle contains the square of its side, so this is a hint to use the cosine law.

$$BF^2=s^2+s^2-2s^2\cos 30^\circ=2s^2(1-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2})=s^2(2-\sqrt{3})$$The area of the equilateral triangle is

$$\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}BF^2=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}s^2(2-\sqrt{3})=\frac{1}{4}s^2(2\sqrt{3}-3)$$Hence, we have that $6\sqrt{3}=s^2\cdot\frac{1}{4}(3+2\sqrt{3}-3)$, giving $s^2=12$, so $s=2\sqrt{3}$. Then the perimeter is $6s=\boxed{\textbf{(C) } 12\sqrt{3}}$.

Problem 15

Recall that the conjugate of the complex number $w = a + bi$, where $a$ and $b$ are real numbers and $i = \sqrt{-1}$, is the complex number $\overline{w} = a - bi$. For any complex number $z$, let $f(z) = 4i\hspace{1pt}\overline{z}$. The polynomial

$$P(z) = z^4 + 4z^3 + 3z^2 + 2z + 1$$has four complex roots: $z_1$, $z_2$, $z_3$, and $z_4$. Let

$$Q(z) = z^4 + Az^3 + Bz^2 + Cz + D$$be the polynomial whose roots are $f(z_1)$, $f(z_2)$, $f(z_3)$, and $f(z_4)$, where the coefficients $A,$ $B,$ $C,$ and $D$ are complex numbers. What is $B + D?$

$(\textbf{A}): {-}304\qquad(\textbf{B}) : {-}208\qquad(\textbf{C}) : 12i\qquad(\textbf{D}) : 208\qquad(\textbf{E}) : 304$

Solution

Consider $g(z)=4iz$. Let $P(z)=(z-r)(z-s)(z-\overline{r})(z-\overline{s})$. Then $Q(z)=P(g(z))=(z-4i\overline{r})(z-4ir)(z-4i\overline{s})(z-4is)$. Then $B=(-4i)^2 \cdot 3 = -48$ while $D=(-4i)^4 \cdot 1=256$. Hence $A+B=-48+256=\boxed{\textbf{(D)} 208}$.

Problem 16

An organization has $30$ employees, $20$ of whom have a brand A computer while the other $10$ have a brand B computer. For security, the computers can only be connected to each other and only by cables. The cables can only connect a brand A computer to a brand B computer. Employees can communicate with each other if their computers are directly connected by a cable or by relaying messages through a series of connected computers. Initially, no computer is connected to any other. A technician arbitrarily selects one computer of each brand and installs a cable between them, provided there is not already a cable between that pair. The technician stops once every employee can communicate with each other. What is the maximum possible number of cables used?

$\textbf{(A)}\ 190 \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 191 \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 192 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 195 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 196$

Solution

Leave one computer out to never be connected until the very end. Doing this on the side with more computers will result in more connections before it.

$19 \cdot 10 + 1 = \boxed{\textbf{(B) } 191}$.

See MRENTHUSIASM’s solution on AoPS for a proof by Pigeonhole Principle.

Problem 17

For how many ordered pairs $(b,c)$ of positive integers does neither $x^2+bx+c=0$ nor $x^2+cx+b=0$ have two distinct real solutions?

$\textbf{(A) } 4 \qquad \textbf{(B) } 6 \qquad \textbf{(C) } 8 \qquad \textbf{(D) } 12 \qquad \textbf{(E) } 16 \qquad$

Solution

Take the discriminants to be nonpositive: $b^2-4c\le 0$ $c^2-4b\le 0$

Graphing, you can count 6 lattice points between $y=\frac{x^2}{4}$ and $y=2\sqrt{x}$ for $x\ge 0$.

Or, if graphing is not feasible, then solve for one variable and just bash. (Solution by MRENTHUSIASM)

$b^4 \le 16c^2 \le 64b$ Case $b=1$: $1 \le 16c^2 \le 64 \implies c=1,2$ Case $b=2$: $16 \le 16c^2 \le 128 \implies c=1,2$ Case $b=3$: $81 \le 16c^2 \le 192 \implies c=3$ Case $b=4$: $256 \le 16c^2 \le 256 \implies c=4$

$\boxed{\textbf{(B) } 6}$.

Problem 18

Each of $20$ balls is tossed independently and at random into one of $5$ bins. Let $p$ be the probability that some bin ends up with $3$ balls, another with $5$ balls, and the other three with $4$ balls each. Let $q$ be the probability that every bin ends up with $4$ balls. What is $\frac{p}{q}$?

$\textbf{(A)}\ 1 \qquad\textbf{(B)}\ 4 \qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 8 \qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 12 \qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 16$

Solution

$$\frac{\binom{20}{3,5,4,4,4}\binom{5}{1,1,3}}{\binom{20}{4,4,4,4,4}}=\frac{\frac{5\cdot 4}{3!5!}}{\frac{1}{4!4!}}=4 \cdot 4 = \boxed{\textbf{(E) }16}.$$A genius equivalence class solution assumes distinguishability of balls and bins. Then, we compare the number of ways to go from state $4,4,4,4,4$ to state $3,5,4,4,4$ and vice versa.

Case 1: Going from $4,4,4,4,4$ to $3,5,4,4,4$. $5 bins \cdot 4 balls \cdot 4 bins = 80$ ways. Case 2: Going from $3,5,4,4,4$ to $4,4,4,4,4$. $1 bin \cdot 5 balls \cdot 1 bin = 5$ ways.

Hence, the ratio is $80/5=16$.

Problem 19

Let $x$ be the least real number greater than $1$ such that $\sin(x) = \sin(x^2)$, where the arguments are in degrees. What is $x$ rounded up to the closest integer?

$\textbf{(A) } 10 \qquad \textbf{(B) } 13 \qquad \textbf{(C) } 14 \qquad \textbf{(D) } 19 \qquad \textbf{(E) } 20$

Solution

Imagine $2$ points racing each other along the unit circle starting from $1^\circ$ with one moving faster. Then the first point where the sines are equal should be a reflection about the $y$-axis.

Hence, let $x^2=180-x$, so $x^2+x-180=0$. The roots are $\frac{-1\pm\sqrt{1-4(1)(-180)}}{2}=\frac{1\pm\sqrt{721}}{2}$. We are interested in numbers greater than $1$ (positive), so keep the plus only: $x=\frac{1+\sqrt{721}}{2}$. Recalling that $729=3^6=27^2$, we know that $26<\sqrt{721}<27$, such that $25<-1+\sqrt{721}<26$, and $12.5<x<13$, meaning that $\text{round}(x)=\boxed{\textbf{(B) } 13}$.

Problem 20

For each positive integer $n$, let $f_1(n)$ be twice the number of positive integer divisors of $n$, and for $j \ge 2$, let $f_j(n) = f_1(f_{j-1}(n))$. For how many values of $n \le 50$ is $f_{50}(n) = 12?$

$\textbf{(A) }7\qquad\textbf{(B) }8\qquad\textbf{(C) }9\qquad\textbf{(D) }10\qquad\textbf{(E) }11$

Solution

If $n=p_1^{e_1}p_2^{e_2}\dots p_k^{e_k}$, then $f_1(n)=2(e_1+1)(e_2+1)\dots(e_k+1)$. Note that $n=12$ is a fixed point. Work backward: suppose $f_{50}(n)=f_1(f_{49}(n))=12$. Then $f_{49}(n)$ must have $(e_1+1)(e_2+2)\dots(e_k+1)=\frac{12}{2}=6$. We write out the cases for factorizations of $6$, then fit primes while $n\le 50$.

Cases $f_{49}(n)$:

- $2 \cdot 3 \implies$

- $2^1 3^2=18$

- $2^1 5^2=50$

- $3 \cdot 2 \implies$

- $2^2 3^1=12$

- $2^2 5^1=20$

- $2^2 7=28$

- $2^2 11=44$

- $3^2 5^1=45$

- $6 \implies$

- $2^5=32$

Count: $8$.

For $f_{48}(n)$, we will further consider factorizations of half of these, so $9,25,6,10,14,22,16$.

Cases $f_{48}(n)$: Case $9$:

- $3 \cdot 3 \implies 2^2 3^2=36$

Case $25$: no solutions Case $10$:

- $5 \cdot 2 \implies 2^4 3^1=48$

Case $14$: no solutions Case $22$: no solutions Case $16$: no solutions Count: $2$.

For $f_{47}(n)$, we will consider factorizations of half of these, so $18,24$.

Cases $f_{47}(n)$: Case $18$: no solutions Case $24$: no solutions

Hence the total is $8+2=\boxed{\textbf{(C) } 10}$.

Problem 21

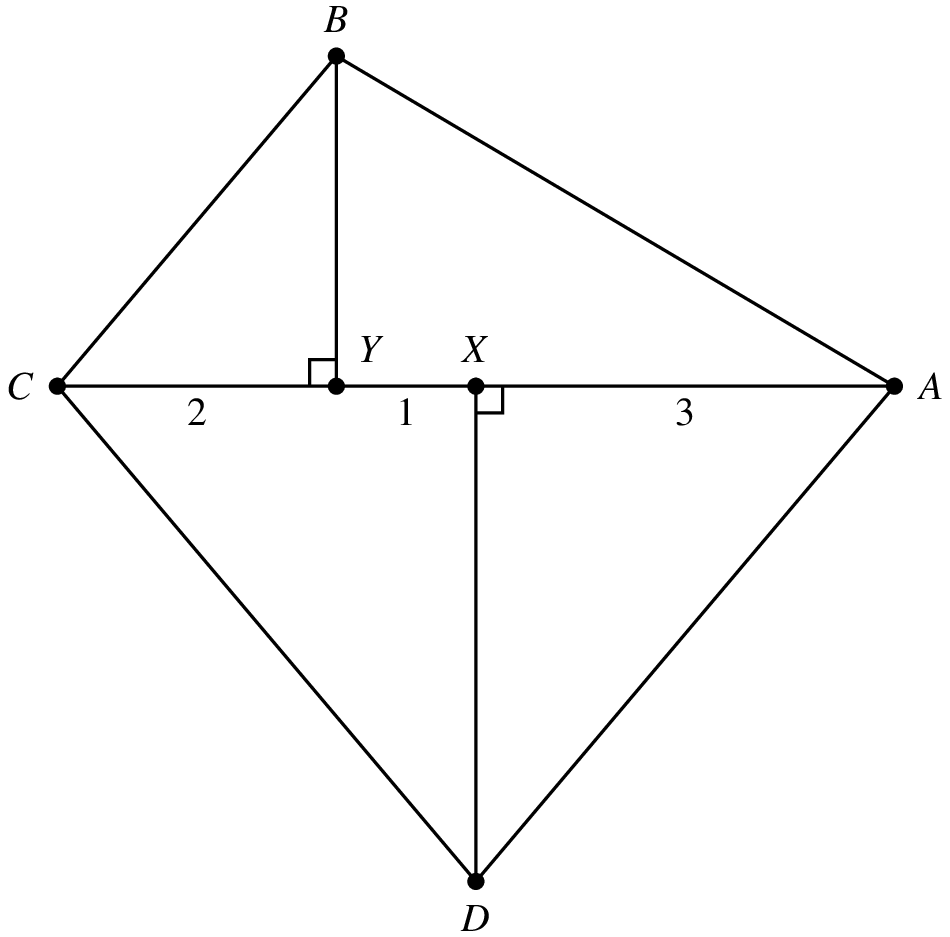

Let $ABCD$ be an isosceles trapezoid with $\overline{BC} \parallel \overline{AD}$ and $AB=CD$. Points $X$ and $Y$ lie on diagonal $\overline{AC}$ with $X$ between $A$ and $Y$, as shown in the figure. Suppose $\angle AXD = \angle BYC = 90^\circ$, $AX = 3$, $XY = 1$, and $YC = 2$. What is the area of $ABCD$?

$\textbf{(A)}: 15\qquad\textbf{(B)} : 5\sqrt{11}\qquad\textbf{(C)} : 3\sqrt{35}\qquad\textbf{(D)} : 18\qquad\textbf{(E)} : 7\sqrt{7}$

$\textbf{(A)}: 15\qquad\textbf{(B)} : 5\sqrt{11}\qquad\textbf{(C)} : 3\sqrt{35}\qquad\textbf{(D)} : 18\qquad\textbf{(E)} : 7\sqrt{7}$

Let $h:=BY+XD$. Then $[ABCD]=\frac{1}{2}h\cdot 6=3h$. But by symmetry, $BD=CA=6$, such that by Pythagoras, $h=\sqrt{6^2-1^2}=\sqrt{35}$. Hence, $[ABCD]=\boxed{\textbf{(C) } 3\sqrt{35}}$.

Solution

Problem 22

Azar and Carl play a game of tic-tac-toe. Azar places an $X$ in one of the boxes in a $3$-by-$3$ array of boxes, then Carl places an $O$ in one of the remaining boxes. After that, Azar places an $X$ in one of the remaining boxes, and so on until all boxes are filled or one of the players has of their symbols in a row—horizontal, vertical, or diagonal—whichever comes first, in which case that player wins the game. Suppose the players make their moves at random, rather than trying to follow a rational strategy, and that Carl wins the game when he places his third $O$. How many ways can the board look after the game is over?

$\textbf{(A) } 36 \qquad\textbf{(B) } 112 \qquad\textbf{(C) } 120 \qquad\textbf{(D) } 148 \qquad\textbf{(E) } 160$

Solution

Draw the diagram, placing the 3 O’s for win and then choose 3 spots out of 6 for X’s. For non-diagonal wins, you have to ensure that you cannot select either of the 2 winning lines for X’s.

$8\binom{6}{3}-6(2)=160-12=\boxed{\textbf{(D) } 148}$.

Problem 23

A quadratic polynomial with real coefficients and leading coefficient $1$ is called $\emph{disrespectful}$ if the equation $p(p(x))=0$ is satisfied by exactly three real numbers. Among all the disrespectful quadratic polynomials, there is a unique such polynomial $\tilde{p}(x)$ for which the sum of the roots is maximized. What is $\tilde{p}(1)$?

$\textbf{(A) } \frac{5}{16} \qquad\textbf{(B) } \frac{1}{2} \qquad\textbf{(C) } \frac{5}{8} \qquad\textbf{(D) } 1 \qquad\textbf{(E) } \frac{9}{8}$

Solution

This one is very interesting. Once you understand it, it becomes very easy. Namely, draw a graph to visualize, it helps a lot.

Let $r<s$ be the roots of $\tilde{p}(x):=f(x):=x^2+bx+c$. The objective becomes $f(1)=1+b+c$.

Then we wish to have $f(f(x))=0$, meaning $f(x)=r$ or $f(x)=s$. Notice that graphically, this looks like drawing 2 horizontal lines intersecting the graph of $f(x)$ at $y=r$ and $y=s$. The only way you can have $3$ solutions is if the top line intersects 2 points (by symmetry) and the bottom line intersects exactly one point, i.e. the line $y=r$ must intersect the vertex at $x=\frac{r+s}{2}=\frac{-b}{2}$.

Writing our constraint more explicitly:

$f(\frac{-b}{2})=-\frac{b^2}{4}+c=r$.

We want to maximize the sum of roots, which by Vieta’s formulas is equal to $-b$. We will write $-b$ as a function of a single variable to minimize.

$(s+r)^2-4rs=-4r$ $(s-r)^2=-4r$ $s-r=2\sqrt{-r}$ since $s>r \iff s-r>0$ $-b=s+r=(s-r)+2r=2(r+\sqrt{-r})$

This is a quadratic in $t=\sqrt{-r}$ of the form $2(-t^2+t)$ with minimum at $\sqrt{-r}=\frac{-1}{2(-1)}=\frac{1}{2}$ or $r=\frac{-1}{4}$, so $s=r+2\sqrt{-r}=\frac{3}{4}$. Hence, $f(1)=(1-\frac{3}{4})(1-(-\frac{1}{4}))=\boxed{\textbf{(A) } \frac{5}{16}}$.

Note: using vertex form of the parabola, it turns out that this calculation simplifies so much and removes the need for bashing. Let $f(x):=(x-h)^2+k$, such that we maximize $2h$, equivalent to maximizing $h$. Then $0=f(f(h))=f(k)=(k-h)^2+k=k^2-2kh+h^2+k$.

The trick is to notice the middle coefficient has term $2h$ while the constant coefficient has an expression in $h^2$, so in the discriminant everything will cancel out to a nice linear inequality.

$k^2+(1-2h)k+h^2=0$. The discriminant must be nonnegative to have solutions. $(1-2h)^2-4h^2\ge 0$. $h\le \frac{1}{4}$, so set $h=\frac{1}{4}$, such that $\Delta = 0$. Then $k=-\frac{1-2h}{2}=\frac{-1}{4}$, so $f(1)=\frac{5}{16}$.

Problem 24

Convex quadrilateral $ABCD$ has $AB = 18, \angle{A} = 60^\circ,$ and $\overline{AB} \parallel \overline{CD}.$ In some order, the lengths of the four sides form an arithmetic progression, and side $\overline{AB}$ is a side of maximum length. The length of another side is $a.$ What is the sum of all possible values of $a$?

$\textbf{(A) } 24 \qquad \textbf{(B) } 42 \qquad \textbf{(C) } 60 \qquad \textbf{(D) } 66 \qquad \textbf{(E) } 84$

Solution

I computed based on the diagram that

$$(AB - \cos(60^\circ)AD - CD)^2 + (\sin(60^\circ)AD)^2 = BC^2.$$In actuality, this simplifies to the cosine law, which is the simpler way to interpret the diagram by translating $BC$:

$$(18 - CD)^2 + AD^2 - 2(18-CD)AD\cos(60^\circ) = BC^2.$$Since $\cos(60^\circ) = \frac{1}{2}$, we can simplify to:

$$(18 - CD)^2 + AD^2 - (18-CD)AD = BC^2.$$This is now the part that requires some forward-thinking for an efficient solution. First, let’s simplify the notation. Let $a=AD,b=BC,c=CD$. Then we have that

$$(18-c)^2+a^2-(18-c)a=b^2.$$How should we factor this efficiently? Recall that we have an arithmetic progression, such that $BC,CD,DA$ will be a permutation of $18-k,18-2k,18-3k$. So we want to have a difference between 2 terms on each side of the equation so that we are left with some multiple of $k$, which will cancel on both sides and leave us with only an affine equation to solve rather than a quadratic equation.

The following works for this purpose:

$$(18-c)(18-c-a)=(b-a)(b+a). \qquad (*)$$Now, we could consider the $3!=6$ permutations of $a,b,c$, but there is a very clever symmetry argument here (solution 2 on AoPS). Consider the arithmetic sequence ${18-k,18-2k,18-3k}$. Now look at these colorings:

$$\textcolor{blue}{18-3k},\textcolor{red}{18-2k},\textcolor{blue}{18-k},\textcolor{red}{18}$$ $$\textcolor{blue}{18-3k},\textcolor{blue}{18-2k},\textcolor{red}{18-k},\textcolor{red}{18}$$As you can see, in an arithmetic progression of $4$ terms, in both these cases, the absolute difference between the colored terms is equal. The only remaining case is:

$$\textcolor{blue}{18-3k},\textcolor{red}{18-2k},\textcolor{red}{18-k},\textcolor{blue}{18}$$First, we take care of the trivial case $k=0$. In this case, we add $\colorbox{yellow}{18}$ as a value to the answer.

Hence, we can break the casework in $18-c$, and plug into $(*)$ to find solutions.

- $18-c=3k$

- $18-c\ne 3k$

Case 1: $18-c=3k$ Case 1.1: $a=18-2k$, $b=18-k$ $3k(5k-18)=k(36-3k) \implies k=5$, yielding $13+8+3=3\cdot 8=\colorbox{yellow}{24}$. Case 1.2: $a=18-k$, $b=18-2k$ $3k(4k-18)=-k(36-3k) \implies k=2$, yielding $16+14+12=3\cdot 14=\colorbox{yellow}{42}$.

Case 2: $18-c\ne 3k$ Then either $b-a=18-c$ or $b-a=-(18-c)$. Case 2.1: $b-a=18-c$ Then $()$ simplifies to $18-c-a=b+a$, contradicting $18-c-a=b-2a<b+a$. Case 2.2: $b-a=-(18-c)$ Then $()$ simplifies to $18-c=-b$, contradicting $18-c>0>-b$.

Hence, the answer is $18+24+42=\boxed{\textbf{(E) } 84}$.

Problem 25

Let $m\ge 5$ be an odd integer, and let $D(m)$ denote the number of quadruples $(a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4)$ of distinct integers with $1\le a_i \le m$ for all $i$ such that $m$ divides $a_1+a_2+a_3+a_4$. There is a polynomial

$$q(x) = c_3x^3+c_2x^2+c_1x+c_0$$such that $D(m) = q(m)$ for all odd integers $m\ge 5$. What is $c_1?$

$\textbf{(A)}\ {-}6\qquad\textbf{(B)}\ {-}1\qquad\textbf{(C)}\ 4\qquad\textbf{(D)}\ 6\qquad\textbf{(E)}\ 11$

Solution

The first thing we notice that we are given 4 variable numbers, but the answer is a cubic polynomial, hinting that there are actually only 3 degrees of freedom. What explains this?

Let’s identify the constraints:

- $m \ge 5$ is an odd integer.

- Equivalently, $m = 2k+1$ for some integer $k \ge 2$.

- Each $a_i$ is a distinct integer in ${1,2,\dots,m}$.

- $m | (a_1+a_2+a_3+a_4) \iff a_1+a_2+a_3+a_4 \equiv 0 \pmod m$

Aha! Fixing 3 variables determines the last one uniquely since there is only one integer from $1$ to $m$ that will satisfy the condition:

$$a_1 \equiv -(a_2+a_3+a_4) \pmod m$$This is because the set ${1,2,\dots,m}$ forms a complete residue system mod $m$.

Since the $a_i$ are all distinct, determining our $a_i$ is equivalent to selecting permutations from the set ${1,2,\dots,m}$. The last one is determined by the first 3, so we pick 3 numbers. The number of possibilities is given by:

$$_m P _3 = m(m-1)(m-2).$$But wait! The last number could collide with the first 3 and break the distinctness.

Let our numbers picked be $a,b,c$ in any order, and let $d$ be the last number. We require $d \notin {a,b,c}$. To calculate this, we can use a complementary approach: consider if $d$ clashes with one of the first 3.

Notice the symmetry in the permutations: the cases $d=a$, $d=b$, $d=c$ are equivalent in probability. WLOG, let $d = a$. We will multiply the probability by 3 at the end. which are disjoint equivalent cases. Then the condition for failure is:

$$a+b+c+a \equiv 0 \pmod m$$ $$2a+b+c \equiv 0 \pmod m$$What is the probability that $2a+b+c$ is divisible by $m$? It seems hard to find. But we have yet to use our remaining condition: 1) $m$ is an odd integer $\ge 5$.

This is the key step that is the hardest to find: imagine picking a quadruple $(a,a,b,c)$, each number represented on a circle of integers $1$ to $m$, then skewering all these circles onto one axis.

Then, imagine rotating this skewer on its axis. There are $m$ possible rotations, and each rotation is a valid quadruple. The trick is to realize that out of the $m$ possible rotations, exactly $1$ is valid, i.e. $2a+b+c \equiv 0 \pmod m$. This is because, if you imagine the sum rotating around the clock of $0$ to $m-1$ by $4$ at a time for each rotation of the skewer, then we will cover all numbers ${0,1,\dots,m-1}$ exactly once.

Formally, you can justify this by defining a bijection as follows: for a given quadruple $a,a,b,c$, we can define a rotation as the mapping

$$R: (a,a,b,c) \mapsto (a+1,a+1,b+1,c+1)$$Let $x=(a,a,b,c)$, $s(x)=2a+b+c$. Notice that $s(R(x))=2(a+1)+(b+1)+(c+1)=s(x)+4$. In general, for the $n-th$ rotation, the sum becomes $s(x)+4n$. Remember, we want $s(x)+4n \equiv 0 \pmod m$.

The second critical step is to notice that $4$ and $m$ must be coprime, since $m$ is odd. This implies that $4$ is invertible modulo $m$.

But finally, this means that $s(x)+4n \equiv 0 \pmod m$ for exactly one rotation configuration $n \in {0,1,\dots,m-1}$, as it is uniquely determined by

$$n \equiv -4^{-1} s(x) \pmod m.$$Hence, the probability that $2a+b+c$ is divisible by $m$ is exactly $\frac{1}{m}$. The probability of distinctness for $d$ from $a,b,c$ is $1 - 3 \cdot \frac{1}{m} = \frac{m-3}{m}$.

Our final polynomial becomes:

$$D(m) =m(m-1)(m-2) \cdot \frac{m-3}{m} = (m-1)(m-2)(m-3)$$The linear coefficient is $(-1)(-2)+(-1)(-3)+(-2)(-3) = \boxed{\textbf{(E) }11}$.

Alternative Paths

Key Insights

- While there are 4 variable numbers, the answer is a cubic polynomial, hinting that we are constrainted to only 3 degrees of freedom.

- Noticing the rotational symmetry, we can create equivalence classes with one valid quadruple in each class to calculate the number of valid cases.

Fragile Assumptions

- Here, $m$ must be an odd integer. The $\ge 5$ condition is simply to ensure we can select a quadriple. In fact, we can prove that $D(m) \ne q(m)$ for any even integer $m \ge 4$.

Non-Fragile Assumptions

- The $a_i$ are distinct integers in ${1,2,\dots,m}$. The same solution works if we allow duplicates, but the problem in fact becomes much easier since there is much more structured symmetry so the equivalence classes are trivial to form, directly giving $D(m)=\frac{m^4}{m}=m^3$ for all $m$, odd or even.

Alternative Paths

- Direct Attack

If you are familiar enough with this type of problem, you might immediately recognize the approach of equivalence classes. MRENTHUSIASM’s solution on AoPS is an example of this: he directly forms equivalence classes from all quadruples, finding $D(m)=\frac{1}{m}m(m-1)(m-2)(m-3)$ for odd $m$ since $\gcd(m,4)=1$.

- Complementary Counting

Instead of using probability and symmetry arguments, we can directly use the principle of inclusion-exclusion. The total number of quadruples is $m(m-1)(m-2)(m-3)$, and we want to find the number of valid quadruples.

A valid quadruple is one that satisfies $d \equiv -(a+b+c) \pmod m$, so let our events be $A := (d = a)$ which are all equal in size. We have 3 such copies for $d=a$, $d=b$, $d=c$. Since $d=a$, we have:

$$-2a \equiv b+c \pmod m$$As before, we can use a rotation argument to see the equivalence of cases, so consider the case $a=0$. We have $(1+m-1),(2+m-2),\dots,(m-1+1)$, so $m-1$ cases. In general, the case where $b\equiv c \equiv -a \pmod m$ is excluded.

Now, consider which $a$ values are valid. We have from $1$ to $m$ such values, but it must be different from $b$ and $c$. Hence, there are $m-2$ valid $a$ values.

The bad cases are hence $3(m-1)(m-2)$ cases. Hence, the total number of cases is $m(m-1)(m-2)-3(m-1)(m-2)=(m-1)(m-2)(m-3)$.

- Sum of First Perfect Squares

Unfinished idea: let $m=2n+1$, biject ${1,2,\dots,m}$ to ${-n,\dots,n}$ (still a complete residue system). WLOG let $a<b\le 0\le c<d$ (multiply by 4!). Cases: $c=0$ or $c>0$ (similarly for $b$ by symmetry). Counting cases for $c>0$ including cases with potential clashes between $a,b,c,d$, we get $2[1^2+2^2+\dots+(n-1)^2]$. By symmetry in $(a,b)$ and $(c,d)$ we divide by 2. Also, the number of cases where $a,b,c,d$ clash with $c>0$ is equivalent to the number of cases where $c=0$. Hence the answer is $4![1^2+2^2+\dots+(n-1)^2]=(m-1)(m-2)(m-3)$.

- Generating Function

We can bash with generating functions.

We count ordered quadruples $(a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4)$ of distinct integers from ${1,2,\dots,m}$ whose sum is divisible by $m$ using generating functions and a roots-of-unity filter.

Step 1: Generating Function

Define the bivariate generating function:

$$ F(z,x) = \prod_{a=1}^{m} (1+z\,x^a), $$where $z$ marks chosen elements and $x$ records their sum. The coefficient $[z^4]F(z,x)$ counts 4-element subsets of ${1,2,\dots,m}$ with sum $k$.

The generating function for ordered quadruples is:

$$ G(x) = 24 \cdot [z^4]F(z,x). $$Step 2: Extracting Multiples of $m$

To count sums divisible by $m$, we apply a roots-of-unity filter:

$$ D(m) = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{j=0}^{m-1} G(\omega^j), $$where $\omega$ is a primitive $m$th root of unity.

- For $j=0$, $F(z,1) = (1+z)^m$, so $[z^4]F(z,1) = \binom{m}{4}$.

- For $j\neq 0$, $\prod_{a=1}^{m} (1+z\omega^{ja}) = 1+z^m$, contributing zero to $[z^4]$.

Thus,

$$ D(m) = \frac{24}{m} \binom{m}{4} = (m-1)(m-2)(m-3). $$Step 3: Extracting Coefficients

Expanding,

$$ D(m) = m^3 - 6m^2 + 11m - 6. $$Matching with $q(m) = c_3m^3 + c_2m^2 + c_1m + c_0$, we find $c_1 = 11$.

Final Answer:

$$ \boxed{11} $$- Interpolation Bash

Since a cubic polynomial has $4$ coefficients, it suffices to compute $D(m)$ for $4$ values of $m$ and it will interpolate the polynomial by solving a linear system. This is shown in Steven Chen’s solution.

If you are familiar with discrete calculus, you can fit the polynomial directly using 4 consecutive points of odd $m$.

To determine the coefficient $ c_1 $ of the cubic polynomial $ q(m) = c_3m^3 + c_2m^2 + c_1m + c_0 $ such that $ D(m) = q(m) $ for all odd integers $ m \ge 5 $, we use finite differences on the given values of $ D(m) $.

Given values:

- $ D(5) = 4!\cdot 1 = 24 $

- $ D(7) = 4!\cdot 5 = 120 $

- $ D(9) = 4!\cdot 14 = 336 $

- $ D(11) = 4!\cdot 30 = 720 $

If you are astute, you might recognize the sum of the first natural squares pattern:

- $ 1^2 = 1 $

- $ 1^2 + 2^2 = 5 $

- $ 1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 = 14 $

- $ 1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 + 4^2 = 30 $

In this case, let $ n = \frac{m - 3}{2} $. Then $ D(m) = 4! \cdot \frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6} $. Substituting $ n = \frac{m - 3}{2} $:

$$ D(m) = 4 \cdot \frac{(m - 3)}{2} \cdot \frac{(m - 1)}{2} \cdot (m - 2) = (m - 3)(m - 1)(m - 2). $$Expanding gives $ c_1 = 11$.

If you unable to see this, then we proceed as usual with bashing. First, compute the finite differences with step size 2:

- First differences: $ 96, 216, 384 $

- Second differences: $ 120, 168 $

- Third difference: $ 48 $

For a cubic polynomial, the third finite difference is constant and equal to $ 48 $. This gives $ 48 = 6c_3 \cdot 2^3 $, leading to $ c_3 = 1 $.

Next, use the second finite differences to find $ c_2 $. The second difference at $ m = 5 $ is 120:

- The second difference polynomial is $ 24c_3m + 48c_3 + 8c_2 $

- Substituting $ c_3 = 1 $ and solving gives $ 120 = 24 \cdot 5 + 48 + 8c_2 $, leading to $ c_2 = -6 $.

Finally, use the first finite differences to find $ c_1 $. The first difference at $ m = 5 $ is 96:

- The first difference polynomial is $ 6c_3m^2 + (12c_3 + 4c_2)m + (8c_3 + 4c_2 + 2c_1) $

- Substituting $ c_3 = 1 $ and $ c_2 = -6 $, and solving gives $ 96 = 6 \cdot 25 - 12 \cdot 5 - 16 + 2c_1 $, leading to $ c_1 = 11 $.

Thus, the coefficient $ c_1 $ is $\boxed{11}$.

Generalizations And Connections

The linear coefficient is a Stirling number of the first kind, specifically $s(3+1,3-1)=s(4,2)$. We know that for symmetric polynomials, $e_1^2=e_2+2c_1$, such that $c_1=\frac{e_1^2-e_2}{2}$.

We have $e_1=1+2+3=\binom{4}{2}=6$, while $e_2=1^2+2^2+3^2=6\cdot \frac{2\cdot 3+1}{3}=14$. So the final answer is

$$\frac{6^2 - 14}{2} = \boxed{\textbf{(E) }11}.$$